In-memory computing has been part of the fabric of financial services systems for some years, but it is experiencing a revival in interest as recent developments allow for ever greater input/output speeds and the processing of greater volumes of data.

Pete Harris, editor and publisher of Low-Latency.com, led a panel discussion on in-memory technology at the recent Low Latency Summit in London. He set the scene quoting two White Papers by a respected IT analyst; one reported that in-memory technology is 100,000 times faster than hard disk technology, the other that is 3,000 times faster. Which statistic, he asked, is correct?

Against a background view from the panel that speed depends on the task at hand and system architecture, Evgueny Khartchenko, staff application engineer at Intel, presented some specific statistics. Recognising that in-memory offers huge advantages over solid state drives and hard disks, he said an in-memory single circuit could handle 100 gigabytes of data per second, while an PCIe-bus working with solid state drives or a disk array could handle 2.8 Gbytes per second. Random access memory (RAM) offers even more advantage, offering over 100 million I/O operations per second against 450,000 Iops using a hard disk.

He added: “With regard to latency, in-memory is an order of magnitude faster than disk. The advantages of in-memory depend on how small the chunks of data are that are being accessed and the bandwidth you need.” Steve Graves, president and CEO of McObject, noted similar outcomes when benchmarking an in-memory database against a disk-based database.

While the consensus among panel members was that in-memory has much to offer in terms of performance, they did warn that careful decisions need to be made when selecting technology for trading applications and that one size of in-memory does not fit all. Simon Garland, chief strategist at Kx Systems, commented: “It is important to remember that in-memory database technology is totally different to traditional database technology and is designed to do different things.”

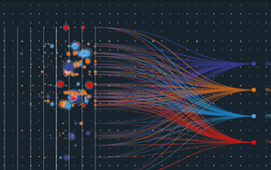

Spencer Greene, chief technology officer for financial services and business manager for global financial exchanges at Tibco Software, added: “In-memory means different things to different people depending on system architecture. Customers who use our solutions for high performance trading systems often start with a traditional database, then move to a database with a cache and then move into RAM. Performance may still not be good enough, so the need is to break down the functionality of the trading system and decide which elements should be in RAM and which should use other data architectures.”

Considering the structure of in-memory technology and its resultant performance, Harris questioned the use of hardware to do the heavy lifting. Khartchenko pointed out that it is not possible to rely entirely on hardware and that software must be considered as part of any solution. Spencer explained: “Putting more processing in hardware in one box, rather than using messaging across wires, will speed up processing dramatically. The more hardware on the same backplane and the less software between solid state drives and RAM the better. To achieve high performance for high frequency trading, it is best to put as much technology close together in the same box as possible.”

If these are some of the technicalities of in-memory computing, Harris asked what are the development challenges? A conference delegate responded, asking the panel what state of the art tools are available to make an application developer’s job easier. Graves suggested there is no need to use anything other than SQL application programming interfaces and drivers that are used to build traditional SQL databases, while Garland suggested the use of SQL or C++ is in many cases determined by company culture and expertise. He concluded: “In-memory computing is also about multi-threaded programming and it is hard to find good developers who can do this.”

Subscribe to our newsletter